The Roman origins

Florence’s rise to power began during the Roman Republic when it was a settlement along the Via Cassia, a major communication route connecting Rome to Cisalpine Gaul. Although its Etruscan origin is debated, more precise traces of its existence appear towards the end of the 1st century BC[1]. Remnants from that era are still evident in the city’s urban layout, particularly in the heart of the city, which follows the regular pattern of the Roman grid (centuriatio o castramentatio), still identifiable today [2].

The location of Florence was strategically chosen. The Via Cassia continued across what would later become the Ponte Vecchio, allowing easy control over key communication routes. Additionally, its proximity to Faesulae (modern-day Fiesole), a city that had supported Catiline in his failed coup in 62 BC, likely influenced Caesar’s decision to establish Florence as a colony for veterans in 59 BC. The Arno River, which flows through Florence, and the Mugnone River, which merges with the Arno, provided another significant logistical advantage. These waterways, navigable and connecting the settlement to the Tyrrhenian port of Pisa, facilitated merchant traffic and contributed to Florence’s rapid growth. By 287 AD, Florence had become the capital of the administrative district of Tuscia et Umbria under Diocletian, and it was established as a bishopric by the early 4th century[3].

From Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages

The history of Florence took a dramatic turn between the 5th and 9th centuries. The city was first besieged by Gothic forces in 405, with Stilicho defending it. As the Western Roman Empire declined and eventually fell, Florence faced a series of crises: the city was occupied by the Byzantines, and later plundered by the Ostrogoth King Totila during the Gothic War (535-553).

Manuscript Chig.L.VIII.296, f.36r

© 2024 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana

It then passed to the Longobards in 570, who made it a duchy, and subsequently to the Franks: Charlemagne celebrated Christmas there in 786 while dealing with complaints about the Lombard duke Guidibrando. However, Lombard rule had decreed the creation of new communication routes, leading to the decline of the Roman ones, including the aforementioned Via Cassia. The first signs of the city’s recovery would not be seen until the reign of Lothair I, King of Italy and later Carolingian Emperor, who made it the center for the training of the Tuscan clergy (825). It was in these decades that we see the construction of a new city wall, which roughly followed the Roman one, probably to prevent the repetition of the plundering by Norman pirates (825) and Hungarian raids (first half of the 10th century)[4].

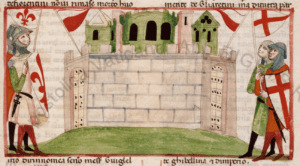

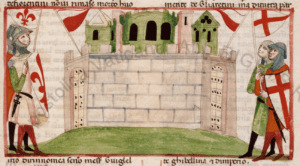

Manuscript Chig.L.VIII.296, f.56r

© 2024 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana

By the turn of the millennium, Florence started accumulating the resources that would drive its future prominence. In 1018, construction began on the Basilica of S. Minato al Monte, honoring the first Christian martyr of Florence[5]. In 1055, a council convened in the city with Pope Victor II and Emperor Henry III the Black in attendance. By the mid-11th century, Florence had become the capital of the Marca of Tuscany under Geoffrey of Lorraine. The tumultuous period at the turn of the 11th and 12th centuries left a significant imprint on Florence, including the regency of the legendary Matilda di Canossa [6], and laid the groundwork for the conflict between the Guelfs and Ghibellines that would dominate Tuscany in the following centuries.

The duality of Guelfs and Ghibellines

Understanding Florence during this era requires a closer examination of the Guelf and Ghibelline factions. Contrary to common oversimplifications, the Ghibellines did not solely support the Empire’s attempts to unify Italy, nor did the Guelfs purely advocate for Papal independence from imperial power. These were local factions, each vying for power and proclaiming allegiance to either the Emperor or the Pope based on who could best support their local ambitions[7].

The origin of these terms, subject to much speculation even in the 14th century[8], is less significant than their impact:

“in provinces and cities where divisions and factions exist, it is necessary that these be named in some way; thus, in the assembly, the most common names are imposed, so to speak; and in this, there is generally no respect for the Church or the Empire, but only for those factions that exist in the city or province”

(Bartolo da Sassoferrato, as cited in Salvemini, 1974, p. 7)[9].

The power struggles in Florence would have been inconsequential without something substantial to fight over. Florence achieved independence from the Marquisate of Tuscany in 1115, following the death of Matilda di Canossa and the extinction of the Cadolingi dynasty, which controlled territories west of the city. This independence sparked a rapid expansion, as Florence began to annex smaller feudal territories and engage in conflicts (and sometimes alliances) with neighboring cities like Pisa [10].

The Florentine Republic: formation and expansion

The establishment of the Florentine Republic in 1138 followed the conquest and destruction of Fiesole, centralizing the population within Florence. In an apparent effort to emulate the Roman model, the city was governed by two Consuls, aided by a council of a hundred counselors who drafted laws and statutes. While still nominally under the influence of the Empire, these “two city consuls and council of the senate” were likely members of the dominant families, composed of the city’s aristocracy and clergy [11] .

The Rise of the Arts

Pic by Sailko, CCA 3.0

The formation of the Arti (guilds) in Florence is complex, with roots in ancient associative practices. Associations of workers, whether merchants or artisans, aimed to protect common interests. These collegia or corpora can be traced back to the Roman Republic[12]. However, during the Late Empire and the Germanic invasions, these associations declined, eventually reverting to simpler forms of workers sharing the same trade[13]. As Florence grew, these associations gained influence and formalized into true corporations. The first documented guild was the Arte dei Mercatanti (Art of Merchants) or di Calimala in 1182, named after the street where their shops were concentrated[14].

Over the following decades, more guilds were established, each with its administrative bodies, headquarters, and emblems. These included the Arts of judges and notaries, wool workers, doctors and apothecaries, silk workers, grocers, furriers, and others, such as second-hand dealers, shoemakers, money changers, stonecutters, carpenters, blacksmiths, and ironworkers[15].

This proliferation of guilds not only strengthened Florence’s economy, attracting the attention of emperors like Henry VI the Cruel or Frederick II of Swabia (and his son Manfredi), but also fueled internal tensions. These tensions would repeatedly erupt into divisions and civil wars within the city over the coming years.

Political evolution and the Podestà system

In 1193, Florence’s government was restructured with the election of Gherardo Caponsacchi as podestà (chief magistrate), replacing the Consuls. The podestà was supposed to be an impartial arbitrator of the city’s political disputes, but this was not always the case. Efforts to appoint outsiders, like Gualfredotto da Milano, as podestà to avoid local biases were largely unsuccessful[16]. The government underwent further changes with the creation of the Primo Popolo, a body composed of various commissions and sub-commissions (consigli and gonfalonieri in terms of the time). This system remained, though with varying success, until 1260, when it was replaced by the government of the Priori delle Arti (Heads of the Arts). These changes in governance, along with the city’s territorial and demographic expansion, were early indicators of the economic growth that would soon make Florence one of the most powerful cities in Europe, where the great merchants at the helm of the guilds became the true rulers of the city.

Times of turbulence: Florence’s path to Dominance

As mentioned earlier, the years between 1138 and 1288 were marked by continuous conflicts over power and territory, with Florence constantly at war with surrounding cities and under the watchful eyes of either the Pope or the Emperor. However, these years also saw steady growth. Florence was described as “in the happiest state it had ever been” by Giovanni Villani[17], with “well-mannered citizens, and very beautiful and adorned women; the most beautiful buildings, full of many necessary arts, beyond other cities of Italy“, as Dino Compagni wrote, perhaps biasedly, having witnessed those years with his own eyes[18].

Manuscript Chig.L.VIII.296, f.60v

© 2024 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana

It is important to note a key event that marked a turning point in the city’s history: the final episode of the Aretine War, which culminated on Saint Barnabas’ Day, Saturday, June 11, 1289. Tensions with Arezzo had escalated after the expulsion of some Guelf families from the neighboring city. When the Aretines discovered that their bishop had attempted to betray them to their rivals, war ensued. After internal discord, which Compagni recounts in detail, the Florentine army, with support from Bologna, Lucca, and Pistoia, marched towards Arezzo through the Casentino. The battle on the plain of Campaldino ended with the Aretines’ defeat, forcing them to retreat within their city walls. Florence emerged stronger, taking another step towards dominance in Tuscany. Although this battle is not the main focus here, it is worth noting that it was particularly bloody and had significant consequences for Florence’s future. Among those on the battlefield that day was a young soldier who experienced “great fear, and in the end, immense joy“[19]: Dante Alighieri.

References

[1] Castagnoli F., La centuriazione di Florentia, in “Universo”, XXVIII, 1948

[2] “Il cardo maximus seguiva grossomodo il tracciato delle attuali via di Calimala e via Roma; il decumanus quello delle via del Corso, degli Speziali e Strozzi. Dove cardo maximus e decumanus s’incrociavano e dove nella vecchia Firenze sorse il Mercato Vecchio e più tardi Piazza Vittorio Emanuele e poi della Repubblica, c’era il Campidoglio” in Cardini F., Breve storia di Firenze, Pacini, 2012.

[3] For sources on the extensive and complex history of Florence, briefly outlined here, refer to Treccani, “Firenze“, in Dizionario di Storia, 2010, and Cardini F., Breve storia di Firenze, Pacini, 2012, pp. 11-88

[4] For the history of Florence, particularly its ancient history, reference is also made to Davidsohn R., Storia di Firenze, unknown translator, G. C. Sansoni Editore, 1907.

[5] Miniato di Firenze, protomartire di Firenze nel 250 circa, si veda Florentine proto-martyr around 250, refer to Berti G. F., Cenni storico-artistici per servire di guida ed illustrazione alla insigne basilica di S. Minato al Monte e di alcuni dintorni presso Firenze, T. Baracchi, 1850.

[6] The magna comitissa Matilda di Canossa (1046-1115) was a prominent figure in the politics of her time. A powerful feudal lord and supporter of the papacy during the Investiture Controversy, her actions significantly influenced the subsequent development of North-Central Italy, as well as its internal divisions. Unable to delve into the depth that this colossal figure deserves here, reference is made to Ghirardini L.L., Storia critica di Matilde di Canossa. Problemi (e misteri) della più grande donna della storia d’Italia, Modena, Aedes muratoriana, 1989.

[7] Salvemini G., Magnati e popolani in Firenze dal 1280 al 1295, Feltrinelli, 1974, p.6.

[8] Villani G., Nuova Cronica, edited by G. Porta, Fondazione Pietro Bembo/Guanda, 1991, Libro Sesto, chapter XXXVIII.

[9] “Hodie vero nomina predicta durant propter alias affectiones. In provinciis et civitatibus, in quibus sunt divisioues et partialitates, necesse est ut diete partes aliquo nomine vocentur; ideo dieta nomina imponuntur tamquam magis coramunia; et in hoc non habetur communiter respectum ad ecclesiam vel imperium, sed solum ad illas partialitates, que in civitate vel provincia sunt.” Bartolo da Sassoferrato, a renowned 14th-century jurist, provides us with this clear image in his treatise De Guelphis et Gebellinis, mentioned in Salvemini G., Magnati e popolani, cit., p.7, translation by the author.

[10] For the events concerning the early years of the Florentine Consulate, as well as its territorial expansion, refer to Cardini F Breve storia di Firenze, cit., pp.30-48 and Villani G., Nuova Cronica, cit., Libro Sesto and Settimo.

[11] Villani G., Nuova Cronica, cit., Libro Quinto, chapter VII.

[12] Cavalli, A. Il fenomeno associativo dai collegia antichi alle corporazioni medioevali, in “Rivista Internazionale Di Scienze Sociali e Discipline Ausiliarie”, vol. 66, no. 262, 1914, pp. 149–76. Available on JSTOR.

[13] Solmi A., “Arti“, in Enciclopedia Italiana, Treccani, 1929.

[14] Cardini F., Breve storia di Firenze, cit., pp.33

[15] Villani G., Nuova Cronica, cit., Libro Ottavo, chapter XIII. In Italian: Arti dei giudici e dei notai, lanaioli, medici e speziali, setaioli e merciari, pellicciai, rigattieri, calzolai, cambiavalute, tagliapietre e carpentieri, fabbri e ferraioli.

[16] Villani G., Nuova Cronica, cit., Libro Sesto, chapter XXXII

[17] “[…]fu nel più felice stato che mai fosse” in Villani G., Nuova Cronica, cit., Libro Ottavo, chapter LXXXIX, translation by the author.

[18] “[…] i cittadini bene costumati, e le donne molto belle e adorne; i casamenti bellissimi, pieni di molte bisognevoli arti, oltre all’altre città d’Italia” in Compagni D., Cronica delle cose occorrenti ne’ tempi suoi, introduction and annotations by Gino Luzzatto, Giulio Einaudi editore, 1968, Libro I, chapter 1, translation by the author.

[19] Barbero A., Dante, Laterza, 2020, Chapter1, translation by the author.