Once upon a time in Florence

Once upon a time in Florence – according to the chroniclers, on Easter Sunday, 10th of April 1216[1] – the knight Buondelmonte of the Buondelmonte family was riding his horse towards Ponte Vecchio, the city’s oldest bridge. He reached the Amidei Tower just before, under the statue of Mars, the ancient Roman god of war, when other knights appeared.

Among them, there were Schiatta of the Uberti family and Oddo Arrighi of the Fifanti. As the knights crossed paths, insults were made. Now, was Buondelmonte who began taunting, or were the others? His thoughts remain unknown; what is known, were the consequences.

The bloody banquet

CC 4.0 – Liz Kxan

Buondelmonte was born in the late twelfth century in the Florentine territories, the son of Tegghiaio di Buondelmonte. From his mention in the Divine Comedy[2], we can infer that he was part of those noblemen from the countryside who began moving into Florence as the city expanded into the surrounding territories. We know very little about him, aside from the main event for which he is remembered in history; in March 1213, in agreement with his brother Gherardo, he sold some of his possessions to the monastery of Passignano. He and his brother are also remembered as patrons of the church of San Lorenzo in September 1213, and in a division of property with the bishop of Florence in August 1214.[3]

The precise chain of events that brought to that fateful Easter is mostly lost to history. Fragments remain, and an anonymous place the onset in January 1215, during the lavish banquet hosted by Mazzingo Tegrimi of the Mazzinghi family to celebrate his investiture as a knight. This feast was organized by the city podestà, Corrado Orlandi, at his castle in Campi Bisenzio. As was customary, all the most prominent families of Florence were invited. There, Buondelmonte was sharing a plate with his friend Uberto of the Infangati, when a jester thought it was a good moment to play a prank. He took the plate from them, but Uberto didn’t laugh.[4]

Oddo Arrighi mocked him, Uberto answered rudely, and the first threw a meat tray in his face. Tensions arose during the rest of the banquet: when the tables were cleared, Buondelmonte took a knife and slashed Otto’s arm. Blood was shed, and it couldn’t be forgotten without tarnishing Otto’s honour. Advised by friends and family, he proposed to ease the tension through marriage: Buondelmonte would have married Otto’s nephew on the 10th of February. Unfortunately, the bride waited in vain for the groom.

The wedding day

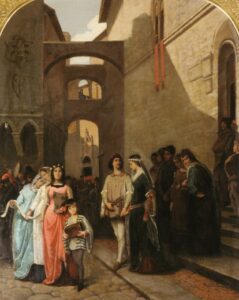

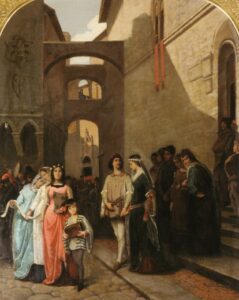

Francesco Saverio Altamura, circa 1858-1860

Oil on canvas

Collezione Banca Carime, Cosenza

On the wedding day, the hot-headed Buondelmonte went instead to the house of the Donati family, where he vowed to marry the beautiful daughter of Forese the Elder and Gualdrada Donati. The insult was too much for the bride’s family and demanded a vendetta, a bloody vengeance. They called for a meeting in the church of Santa Maria Sopra Porta, a building that you can still admire if you ever happen to visit Florence. Some proposed a light vengeance in the form of a beating, or even to disfigure Buondelmonte to console the bride’s father, only to find that he was inconsolable. Mosca of the Lamberti stood up, and added that “if you beat or disfigure him, mind to find a place to hide […] cosa fatta cappa à“. Only things done to the end are done well, and that meant only one thing: Buondelmonte had to die.

The murder, the Guelphs. and Ghibellines

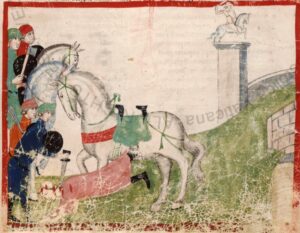

On Easter Sunday 1216, the day chosen for the wedding between him and the daughter of Gualdrada degli Uberti, Buondelmonte reached the tower of the Amidei, close friends of Otto Arrighi. He was dressed at his best for the ceremony: on a horse with a white palfrey, in white clothes, and a garland of flowers on his head. Schiatta degli Uberti “rode towards him, hit with a mace on the head, and unhorsed him[5]“. Oddo Arrighi reached for the crawling Buondelmonte, and being the dishonoured party, had the honour of the final blow, and “with a knife, he cut his veins”. The young Buondelmonte bled to death under the watchful eye of Mars.

Manuscript Chig.L.VIII.296, f.74r

© 2024 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana

The murder drove a wedge between the most eminent Florentine families. On one side were the Uberti, Lamberti, and Amidei families; on the other the Buondelmonti, the Pazzi, and the Donati. Due to the strong loyalty of the Uberti to the Holy Roman Emperor, the rivalry soon exacerbated the ongoing city disputes. If one side supported the Empire, even just vaguely, then the other must be against it, and support the Papacy. This fateful event, although historically dubious, was used by later historians to mark the beginning of the civil war that would drench Florence in the blood of its citizens for the next one hundred years: the feud between Guelphs and Ghibellines.

References

[1] Faini E, Il convito del 1216. La vendetta all’origine del fazionalismo fiorentino, in Annali di Storia di Firenze, Università degli studi di Firenze, 2006, pp. 7-36

[2] Paradiso, Canto XVI, vv. 136-147

“a casa di che nacque il vostro fleto,

per lo giusto disdegno che v’ha morti,

e puose fine al vostro viver lieto,

era onorata, essa e suoi consorti:

o Buondelmonte, quanto mal fuggisti

le nozze sue per li altrui conforti!

Molti sarebber lieti, che son tristi,

se Dio t’avesse conceduto ad Ema

la prima volta ch’a città venisti.”

[3] Berti A., “BUONDELMONTI, Buondelmonte” in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Treccani, 1972

[4] You can find a more detailed examination (in Italian) of this event here, in the post “Cosa fatta capo ha” by Festival del Medioevo.

The event is also mentioned by Dante (Inferno, Canto XXVIII, vv. 106-111):

«gridò: “Ricordera’ ti anche del Mosca,

che disse, lasso!, ‘Capo ha cosa fatta’,

che fu mal seme per la gente tosca”.

E io li aggiunsi: “E morte di tua schiatta”;

per ch’elli, accumulando duol con duolo,

sen gìo come persona trista e matta.»

[5] Villani G., Nuova Cronica, edited by G. Porta, Fondazione Pietro Bembo/Guanda, 1991, Libro Sesto, chapter XXXVIII.