In understanding the economic rise of Florence, it is essential to examine three key phenomena: the gold florin, the textile industry, and financial activities. While the available data are scarce and still under study [1], I’ll try to provide a general overview of these aspects, tracing the city’s transformation from a regional player to a significant economic power in medieval Europe

The spread of Italian mercantile activities across Europe during the Middle Ages, particularly from the Champagne fairs in France to England and Flanders, highlighted a significant challenge: managing commercial operations over vast distances and extended periods. Over the decades, an efficient credit system developed within the Italian mercantile network, facilitating the transfer of debts and credits across time and space through simple bookkeeping [2]. This system laid the foundation for the earliest banking operations and supported the growing international trade that required efficient currency exchange [3].

From the silver denarius to the golden fiorino

At the time, the Carolingian denarius (also called denar or denier)[4], was still in circulation but various other coins had been minted across different territories, each with its own value. We can easily imagine the difficulties this could cause: many coins of different weights, either due to oxidation in use or fraudulent filing of the edges. Nevertheless, the Carolingian denarius remained in circulation for a long time, thanks also to the various mints (albeit few in number) scattered throughout the imperial territory. In Tuscany, the oldest mint was in Lucca (9th century), followed by Pisa (mid-12th century), Siena, Volterra, and Arezzo (end of the 12th century).

The situation was different in Florence, which used the Pisan grosso[5], as Florence supplied at least half of the silver used by the Pisan mint from 1171[6]. Florence continued to use this currency for about fifty years before it began minting the Florentine silver grosso. This coin rapidly spread, replacing the coins of neighboring cities in exchanges with other Italian states [7].

With the growth of economic activities, there was a pressing need for a new currency in gold. After centuries of absence, gold coinage reappeared in Europe, starting with Genoa’s genovino in 1252, closely followed by the Florentine gold florin, or fiorino [8]. Villani gives a precise description of this coin, describing it as “a fine gold coin of 24 carats, called gold florins, and valued at twenty soldi each“[9]. Therefore, a pure gold coin, weighing 3.4-3.5 grams, bearing on one side the image of Saint John the Baptist, and on the other the Florentine fleur-de-lis, valued at 20 soldi, equivalent to 240 denari, or a pound of silver.

The golden age of florentine banks

Saint John the Baptist / Buttoned Fleur-de-lys

S.IOHA NNES B? / +FLOR ENTIA

Courtesy of Marina Fischer, University of Calgary

This coin immediately gained widespread credibility and rapid dissemination [10] facilitating transactions and laying the foundation for the future expansion of trade and the development of the textile industry.

Florence entered its golden age, albeit later than other cities on the peninsula that had already joined the late medieval Italian economic boom, or so scholars hypothesize based on the scarcity of documents. As previously mentioned, it was, after all, excluded from the main communication routes, which had changed during the Lombard domination, and it did not have direct maritime outlets. However, it skillfully exploited the potential offered by the territory: the forests to the east, towards the Apennines, provided access to large quantities of timber, while the plain created by the Arno River allowed for extensive urban expansion, in addition to enabling a relatively easy outlet to the sea. Tuscany itself offered resources all around: the Apennine hills for transhumance, vegetable and mineral dyes in the nearby cities of San Gimignano, Borgo San Sepolcro, and Arezzo, iron and alum deposits on the Elba Island, copper and silver in the vicinity of Siena[11].

Returning to the Arno, its generally stable course was of primary importance in many of the complex stages of wool cloth processing, which during the fourteenth century would become Florence’s largest economic activity.

The textile industry

Florence’s textile industry, particularly in wool, was a crucial driver of its economic growth. Until the 1320s, Florentine wool production was limited and of medium-low quality, primarily serving domestic consumption with some exports to the Levant [12]. The city’s textile industry faced two main challenges: the complexity of wool processing and the dominance of Flemish textiles in the market. Wool processing involved 15-18 stages [13], beginning with the raw material purchased by merchants of the Arte di Calimala, and ending with the dyed and pressed product ready for sale, thanks to water mills powered by the Arno River

This complex production cycle required significant labor, contributing to Florence’s demographic expansion in the late 13th century [14]. However, Florence could not initially compete with Northern European textile producers, such as those in Flanders, whose textiles were of higher quality and fetched higher prices [15]. As often happens, after reaching its peak in 1318, this economic power also had its period of crisis, a period that the Florentine wool merchants knew how to exploit well.

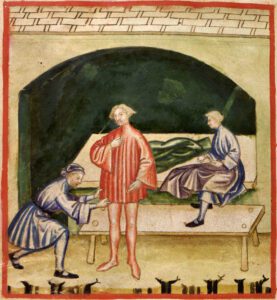

Tacuinum sanitatis (XIV century)

Public Domain

At the end of the 13th century, Florence was not capable of producing textiles at the level of its Northern European competitors, or at least there are no documents to suggest this; the product itself was sold at between 1/3 and 1/2 the price of Flemish textiles[16]. In the early 14th century, the Florentine merchant network supplied the Flemish workshops with high-quality English wool. In 1331, the statute of the Arte della Lana recorded for the first time the production of “panni alla francesca” (French-style cloth): where the primary producer cannot fully meet demand, the secondary producer steps in with a similar and imitative product.

The end of the Grande Daperie

Concurrently, leveraging existing contacts, the merchants of the Arte di Calimala began to meet the growing demand for raw materials from the Arte della Lana, with that portion initially intended for the Flemish markets. During the second half of the 14th century, as the crisis in the North European wool market intensified, Flemish-Brabant workers began to migrate to Florence, bringing fortune to the city and ruin to the Flemish grande draperie[17]. The cycle closed again, as it had been for the paper from the Levant.

The Arte della Lana was not an isolated entity. Although over the centuries it would become the most powerful, employing an increasing portion of the city’s population, its daily operations required the support of other guilds: carpenters and blacksmiths for machinery maintenance, notaries for drafting contracts, and so on[18]. A special relationship existed, as already mentioned, with the Arte di Calimala: for supply and sales, it relied on its merchants and their financial system.

The financial system

The expansion of Florence’s economy was closely tied to the development of its financial system, which evolved from the merchant networks and credit systems of the time. Medieval trade involved significantly longer timelines than today, with production cycles, sea voyages, and land transport taking considerable time. The physical transfer of money was made easier by the introduction of higher-value coins, but it remained complex, slow, and sometimes dangerous. Small merchants could manage their business with little difficulty, but those in higher social ranks, such as managers of Florentine branches abroad, often faced liquidity problems—either having large sums unproductively idle or lacking funds when needed. The solution to these problems was the creation of an early credit system[19].

The roots of this system lay in the passive aspect of the problem, namely, in the company needing to increase its liquid assets to exploit a commercial or productive opportunity it had identified or been offered. Subsequently, the active aspect emerged: when another company, which could be called a “banker”, intervened to meet the needs of the first, thus employing its unused resources, in return for a discount on merchandise purchases (masking what was effectively an interest).

The financial relationship developed and was finalized through the joint interaction of the two actors – the debtor who initiates the operation and the creditor, willing to support it – and materialized at the moment of agreement. We notice the first differences compared to credit as we understand it today: if now it is granted mainly for financial purposes by specialized institutions; at the time, it was granted by commercial activities to other commercial activities. It was used also to extend commercial activities in the long term, in anticipation of a certain number of transactions that were believed likely to subsequently take place.

The credit system and the fiducia

Di Guidingo, Di Borgo and Di Puccio, mint magistrates.

Lily of Florence. Around: + FLOR ENTIA

John the Baptist standing, oak leaves at sides; star above. Around: * + S IOHANNES

Italy, Florence. 1306.

CC A-S 2.5

In a manner not dissimilar to our times, the issue arose of how much credit could be obtained/granted, and what the chances were of it being repaid. An interesting system of fiducia[20], emerges from the study of contemporary documents, granted based on assessments made on the solvency of the applicant, from which derives the modern concept of bank credit.

This innovation, seemingly negligible at first glance, was actually crucial in the evolution of banking systems in subsequent centuries: it replaced tangible security (pledge), streamlined credit procedures by eliminating the need for public deeds, and most importantly, decreed the transition to primarily written financial communication. Thanks to the concept of fiducia applied to the credit system, the problem was solved for those merchants who needed short-term financing in limited amounts to complete individual operations: thus operational credit was born. From this innovation originated a cluster of techniques, tools, and terminologies that can be found in the accounting documents of the 14th century as in those of today: trade credit, overdrafts, bank checks and collection mandates, discounting, and endorsements.

Foreign capital in Florentine banks

Returning to the creditor’s perspective, with the spread of these practices, merchants needed increasingly greater liquidity to be able to grant credit to others in exchange for strong interests, more or less disguised to avoid the accusation of usury [21]. Therefore, they began to attract external capital in addition to their own company funds, offering interest on short-term deposits (similarly to modern certificates of deposit), but above all giving wealthier depositors access to a secure system of international deposit and payment. To provide a practical example of the success of this system, we mention Hugh Despenser the Younger: an advisor to King Edward II of England, who between 1321 and 1326 deposited £9,930[22], in the companies of Bardi and Peruzzi, equivalent to about 1360 years of work for a skilled worker [23].

References

[1] Although eminent scholars have dedicated themselves to researching sources on the Florentine economy prior to the 15th century, few traces from that time have survived. The problem had already emerged in the second half of the 14th century: “e per l’arsione de’ detti fuochi in Firenze arsono molti libri e croniche che più pienamente facieno memoria delle cose passate della nostra città di Firenze, sicché poche ne rimasono” (Villani G., Nuova Cronica, cit., Libro Quinto, chapter XXX). To further complicate the situation, some of the established conclusions on the subject have been called into question by archival work. An example of this is Hoshino’s work regarding the Arte della Lana in Hoshino H, Industria tessile e commercio internazionale nella Firenze del tardo Medioevo, Leo S. Olschki Editore, 2001. While awaiting further clarifications on the subject, please refer to the works of the already mentioned Hidetoshi Hoshino and Richard A. Goldthwaite.

[2] Melis F., La grande conquista trecentesca del ‘credito di esercizio’ e la tipologia dei suoi strumenti fino al XVI secolo in Melis F., “La banca pisana e le origini della banca moderna”, Le Monnier, 1987, pp.307 and following.

[3] Goldthwaite R. A., The Economy of Renaissance Florence, cit., ChapterIII, pp. 203 and following.

[4] The Carolingian denarius is arguably the most important and influential coin throughout the European Middle Ages. Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, gold coinage featuring the reigning monarch’s portrait, with its clear political implications, remained in use for centuries, accompanied by silver coin emissions for local exchanges. This system presented two main problems: the disparity in small currency values across different areas and, more importantly, the difficulty in conducting modest commercial exchanges. Continuing his father’s efforts, Charlemagne introduced a monetary reform throughout the Empire: from the Pyrenees to the Elbe, from Brugge to Rome, there would be a single system based on a defined weight silver coin. From one pound of silver, exactly 240 denarii would be minted: in modern terms, a pound would thus be between 404 and 409 grams, and the denarius 1.6-1.7g, measured at the time as 32 grains of wheat. In a single decision, units of weight and currency were established that would influence the European economy until the French Revolution and that of the United Kingdom until 1971. Therefore, it is not surprising that modern historians define the Carolingian denarius as a “proto-euro”. For further details on Carolingian coinage and its consequences, which cannot be detailed here, refer to Barbero A., Carlo Magno, cit., chapter XII, 4, b.

[5] A silver coin, 19mm, roughly 1.7g, worth twelve denarii. For further reading, refer to Herlihy, D., Pisan coinage and the monetary development of Tuscany, 1150-1250, in “Museum Notes, American Numismatic Society“, 6, 1954, pp. 143–168. Available online through JSTOR.

[6] Goldthwaite R. A., The Economy of Renaissance Florence, cit., p.48-49

[7] The studies of Hidetoshi Hoshino are particularly interesting in this regard (Hoshino H.,I Chiarenti di Pistoia a Cremona, 1256–1261 in Hoshino H. “Industria tessile e commercio internazionale nella Firenze del tardo Medioevo”, cit.), These studies are based on the well-known cartularies of the Cremonese notary Oliviero Ferrarie de Sarolis (Archivio di Stato di Mantova, Archivio dei Gonzaga, busta 79). Here Hoshino highlights the preference of Cremonese merchants for the Florentine grosso, accounting for 54.3% of the total currency handled, although it formally had the same value (twelve denarii) as the grossi of Milan, Bologna, and Pisa.

[8] Cardini F., Breve storia di Firenze, cit., p. 55.

[9] “Tornata e riposata l’oste de’ Fiorentini colle vittorie dette dinanzi, la cittade montò molto in istato e in ricchezze e signoria, e in gran tranquillo: per la qual cosa i mercatanti di Firenze, per onore del Comune, ordinaro col popolo e comune che’ssi battesse moneta d’oro in Firenze; e eglino promisono di fornire la moneta d’oro, che in prima battea moneta d’ariento da danari XII l’uno. E allora si cominciò la buona moneta d’oro fine di XXIIII carati, che si chiamano fiorini d’oro, e contavasi l’uno soldi XX; e ciò fu al tempo del detto messere Filippo degli Ugoni di Brescia, del mese di novembre gli anni di Cristo MCCLII. I quali fiorini, gli otto pesavano una oncia, e dall’uno lato era la ‘impronta del giglio, e dall’altro il san Giovanni” in Villani G., Nuova Cronica, cit., Libro Settimo, chapter LIII, translation by the author.

[10] Cardini F., Breve storia di Firenze, cit., p.55

[11] Goldthwaite R. A., The Economy of Renaissance Florence, cit. p.16-18

[12] The information we have on Florentine wool production during this period is quite scarce, primarily deduced from the study of surviving accounting documents. Quoting Hoshino, “dobbiamo confessare di non sapere quasi nulla […] come, per esempio, il mercato, il livello dei prezzi, il tipo dei prodotti e così via, fatta eccezione per l’organizzazione aziendale”; Hoshino H., in La Produzione laniera nel Trecento, cit., p. 5-7

[13] The wool processing procedure, from raw material to finished product, is exceedingly complex and cannot be adequately covered in this work. Although it pertains to a later period, an interesting description can be found in Ammannati F., Per filo e per segno. L’Arte della Lana a Firenze nel Cinquecento, Firenze University Press, 2020, chapter 5..

[14] The exact number of inhabitants is not known with precision, given the absence of a census at the time. The most reliable estimates suggest a population between 90000 and 130000, based on the urban consumption of grain. The calculations behind these estimates are clearly explained in Salvemini G., Magnati e popolani, cit., p. 37..

[15] For a more comprehensive view of Flemish exports, please refer to Chroley P., The Cloth Exports of Flanders and Northern France during the Thirteenth Century: A Luxury Trade?, in “The Economic History Review”, New Series, Vol. 40, No. 3, 1987, pp. 349-379, while regarding industrial development in Flanders refer to Van Werveke H., Industrial Growth in the Middle Ages: The Cloth Industry in Flanders, in “The Economic History Review”, New Series, Vol. 6, No. 3, 1954, pp. 237-245.

[16] Hoshino H., in La Produzione laniera nel Trecento, cit., p. 5-7 and also Goldthwaite R. A., The Economy of Renaissance Florence, cit. p.27.

[17] Hoshino H., in La Produzione laniera nel Trecento, cit., p. 8-12. We can have an interesting comparison with and earlier statute, available for consultation in Statuto dell’Arte della lana di Firenze: (1317-1319) edited by Anna Maria E. Agnoletti, Le Monnier, 1940.

[18] Limiting ourselves to the more accessible sources, it would be easy to focus exclusively on the major players in the economic life of the time, and that would be a mistake. The achievements of the Arti Maggiori (Greater Arts or Major Guilds) were due to the cumulative efforts of the anonymous crowd of workers and the Arti Minori (Lesser Arts or Minor Guilds). If the face of Florence was the Arte della Lana and the major banking houses, its beating heart was the wine sellers and innkeepers, the construction workers, the second-hand dealers and shoemakers, the leather artisans, the butchers and bakers, the small traders, the salaried workers, and so on down to the slaves. These nameless masses would, over time, attempt to make their voices heard. They deserve more in-depth studies for the importance they have had in Florentine history, but this is not the place for that. For their organization, we refer again to Goldthwaite R. A., The Economy of Renaissance Florence, cit. p.342-405. In the upcoming posts, we will refer to specific readings for the trends in wages after 1348, as well as for the popular uprisings of 1320 and 1378.

[19] The evolution of credit systems, the birth of operating credit, and its spread were of immense importance for the economies of the time and have become, over the centuries, the foundation of the modern banking system. In this post, we have attempted to summarize them in broad strokes, based primarily on Melis F., La grande conquista trecentesca del ‘credito di esercizio’ e la tipologia dei suoi strumenti fino al XVI secolo, cit. p. 310-324

[20] Literally “trust”, meaning how much credit could be given to a certain individual based on its personal wealth, defined as market value of liquid assets, goods and properties.

[21] For centuries, the Catholic Church condemned usury, basing this prohibition on interpretations of Jewish tradition and sacred texts. This condemnation might have been relevant in a context dominated by a predominantly rural and little-monetized economy; however, over time, theologians and canon lawyers debated the legitimacy of interest-bearing loans in particular circumstances, such as wars or dealings with non-Christians. The various Councils of the Church then refined the official position, distinguishing between “usury,” always forbidden, and “interest,” allowed within certain limits, and threatening excommunication for those who tolerated usury. Nonetheless, there is little doubt that interest-bearing loans (sometimes enormous and more or less disguised) were routinely practiced. Even at that time, there was a clear difference between what religion forbade and what was done in everyday life.

[22] Edmund Fryde, The Deposits of Hugh Despenser the Younger with Italian Bankers, in “Economic History Review”, n°70, 1955, pp.344–62, mentioned in Goldthwaite R. A., The Economy of Renaissance Florence, cit. p.206.

[23] £9,930 in 1330 roughly equate to 496,500 working days of a skilled English worker of the time, or (adjusted for inflation) to £7,777,617 in current terms. For data on this estimate and their processing, reference is made to the Currency Converter function available on the website of the National Archives of the United Kingdom, and for inflation adjustment, the Inflation Calculator function of the Bank of England is used. Any inaccuracy is, of course, the author’s.

One Response