A city divided

In examining Florentine politics during the 13th and 14th centuries, the terms Magnati (Magnates/Tycoons) and Popolani (Commoners) frequently arise. However, these terms are often misunderstood, with school textbooks sometimes oversimplifying the social division as merely a rich-poor dualism. This post aims to clarify these concepts, as understanding the distinctions, aspirations, and conflicts of these two groups is essential for comprehending the political, economic, and social conflicts that shaped Florence for nearly two centuries.

The Magnati

Following Salvemini’s approach[1], we begin with the Magnati. A late 13th-century law helps define them: “So that in the future there will be no doubts about [who are] the Powerful, be they Nobles or Magnates, those shall be considered such who [among them] have or have had, in their own family or among their relatives, a knight outfitted in the past twenty years; or those who are commonly considered and regarded as such” [2].

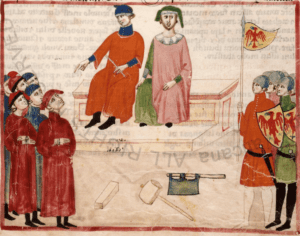

Manuscript Chig.L.VIII.296, f.174r

© 2024 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana

In essence, those wealthy enough to arm a knight were considered Magnati, signifying both prestige and the financial independence necessary to engage in such activities. In a city as wealthy as Florence, where ancient nobles could fall into poverty and “new rich” could rise by knighting their sons, origin became less significant. Writers of the time used the term gentilezza[3] to signify our concept of nobility: those who had a surname (rare at the time) and therefore belonged to a known and ancient lineage (gens, gentis in Latin means “lineage”, “descent”). In summary, the Magnati comprised rich landowners in the countryside and major property owners within the city, including leading figures in the Arte di Calimala and Arte del Cambio.

The Popolani

Turning to the Popolani, it is important not to oversimplify by considering them merely as everyone who was not a Magnate. The Popolo included those involved in the various guilds, especially the Major ones: Judges and Notaries, Merchants of Calimala, Exchange, Wool, Merchants of Por Santa Maria, Physicians and Apothecaries, and Furriers. In modern terms, these were entrepreneurs, professionals, and self-employed workers who actively participated in political life, unlike the broader population, which included the rural populace and lower manual laborers: “laboratores, laborantes, pactoales, subpositi, operarii”[4].

The contrast between Magnati and Popolani has been interpreted in various ways, but we will focus on the economic origins of their conflict. During the 13th century, Florence’s population increased significantly, leading to higher food consumption and increased population density, which in turn drove up rents. These two factors—food supply and rents—became central to the tension between the two groups.

Food and Rents

The Florentine countryside could not support even half of the city’s food demand (about 98 tons daily)[5], forcing the city to rely on external supplies. To address this, Florence implemented legislation to intensify agricultural production, regulate workers’ wages, and encourage imports while prohibiting exports. This situation created a clear conflict between the Magnati, landowners who would have had an interest in a less regulated market, and the Popolani: both the rich, the Popolo Grasso (literally “fat commoners” or “fat people”) among whom were counted the importers of agricultural products, and the commoners, namely the Popolo Minuto (literally “minute people”) who worked daily to literally bring bread home.

Moving on to the issue of rents, we remember that the major Florentine property owners were considered Magnati, and would have had everything to gain from the sudden increase in the demand for rents for shops, and the consequent increase in prices caused by the limited number of commercial properties available.

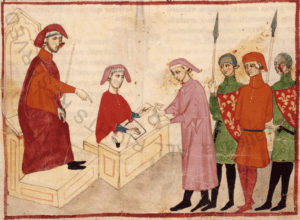

Manuscript Chig.L.VIII.296, f.56r

© 2024 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana

The opposite view would have been held by the Popolani, who wanted their demands satisfied, but an excessive cost of rents would clearly have harmed their businesses. We can hypothesize this situation by looking at the Statuto di Calimala of 1302, where we find mentioned an interesting custom: the Consuls of Calimala, on January 2 of each year, had to expressly ask the property owners if they were fine with keeping the rent price the same as the previous year. Obviously, this situation did not last long, and soon laws appeared to the detriment of the owners, who would no longer be able to evict tenants at will. Beyond economic motivations, personal rivalries and power struggles also fueled the animosity between Magnati and Popolani.

When political competition or personal exploitation of internal party divisions was insufficient, violence ensued, from inciting the working population to armed street battles. For both Magnati and Popolani, “victory or defeat were a matter of life or death”[6].

New laws: the Ordinamenti di Giustizia

This longstanding tension found a partial resolution following the Battle of Campaldino. Initially, some Magnati, confident that their military contributions had secured the victory, attempted to dominate city politics, committing “many wrongs against the Popolani, beating them, and other villainies”[7]. In response, the Popolani, led by Giano della Bella[8], a wealthy Guelf merchant from the Arte di Calimala, began to consolidate their power. Bella, who had fought valiantly at Campaldino, was soon elected among the Priori, the highest political office in Florence. From 1292 to 1295, he became the Popolani’s spokesperson, driving the passage of laws[9] that severely limited the Magnati’s political power and placed them at a disadvantage in both civil and criminal matters.

Manuscript Chig.L.VIII.296

Public Domain

These efforts culminated on January 18, 1293, with Ordinamenti di Giustizia (“Orders of Justice”). It was a new set of laws “against the powerful who wronged the Popolani: and that one consort was held for the other; and that the crimes would be proven by two witnesses of public voice and fame: and they deliberated that whichever family had had knights among them, all will be considered Grandi [magnates], and that they could not be part the Signoria [governing authority], nor Gonfaloniere di Giustizia [head of internal security forces], nor of their collegi [their asisstants] […] and they ordered that the old Signori [members of the government], and specific arroti [magistrates’ clerks], were to elect the new ones“[10].

Despite efforts to resist these laws through legal and violent means, the Magnati were ultimately unsuccessful. However, Bella’s popularity was short-lived; his zealous actions against the powerful alienated former allies, leading to a political conspiracy[11] that forced him into exile; he died in France in the early 14th century.

Florence in the Hands of the Popolani

While the Ordinamenti di Giustizia formally excluded the Magnati from key governmental positions, their influence in Florentine politics remained significant due to their economic resources, client networks, and military power. However, Florence was now officially governed by the Popolani, specifically the wealthiest and most influential among them: the Priori delle Arti. The Priori held the highest legal and political authority, overseeing all public officials of the Republic. Although the system of election was formally in place, it was effectively oriented toward maintaining the ruling group in power in an oligarchic manner. To prevent individual power grabs, the Priori served only two-month terms, resided in public buildings like the Torre della Castagna and later the Palazzo del Bargello[12]), and were maintained at the city’s expense under strict communication restrictions to ensure their impartiality [13].

In the year 1300, Dante Alighieri, representing the Arte dei Medici e degli Speziali, was elected as one of the Priori [14]. Less than two years later, he was condemned for embezzlement, forgery, and extortion (among other charges), fined 5000 florins, and permanently excluded from public office, leading to his exile under penalty of death if captured. This politically motivated conviction marked the conclusion of the struggle between the Guelfi Bianchi (White Guelfs) and Guelfi Neri (Black Guelfs).

Black and White Guelfs

The division between the Guelfi Bianchi and Guelfi Neri emerged after the Ordinamenti di Giustizia, rooted in the internal disputes of the Cancellieri family of Pistoia, which quickly spread to Florence[15]. Two families symbolized and stirred the two respective factions, both from the district of Porta San Piero.

Casa di Dante, Florence.

Pic by Sailko, CCA 3.0

Leading the Whites were the Cerchi: an extremely wealthy merchant family[16], but new in their role and inexperienced in the complex system of influences that allowed them to intimidate their enemies and keep their friends close[17].

On the other side were the Donati: wealthy, but not even remotely comparable to the economic power of their rivals. This wasn’t the only difference, in fact, the Donati were an ancient family well-versed in the art of Florentine politics, aided by a bad reputation for violence[18]. Soon under these families, various parts of the city society began to align themselves, each in the hope that the winner could advance their interests, and to bring to a head all the issues left unresolved by the parenthesis of Giano della Bella. Thus, those nostalgic for the latter, dissatisfied with the regime’s perceived “moderate turn,” aligned with the Whites, and with them the old families of Parte Ghibellina (the Ghibelline party), who had not yet forgotten the affront of exclusion from political life at the hands of the wealthy Guelf families, including the Donati[19].

Relief from Santa Maria Novella church in Florence, outside view.

Pic by Sailko, CCA 3.0

Soon, episodes of violence began: during a brawl, a young Cerchi had his nose cut off, then a narrowly avoided brawl during a funeral, and the attempted murder of Guido Cavalcanti, followed by his failed revenge against Corso Donati. In a short time, while the regime di Popolo (Government of the People) risked collapsing, Florence found itself on the brink of a civil war. The Blacks, however, had an ace up their sleeve: the extremely powerful Pope Boniface VIII, who at the time governed the Church of Rome with an iron fist. He sent a cardinal to mediate peace. It is not known why he made this decision, but it is hypothesized that the Pope had no interest in seeing the most powerful city of Tuscany plunge into chaos; the fact that the papal finances were partially managed by the Spini, Florentine bankers and Black Guelfs, might have motivated him to intervene[20].

The fact remains that the negotiations failed: it is uncertain whether the Cardinal was sent to the city with the hidden purpose of favouring the Blacks, but he left in anger, casting an interdict on the city. Not even the Whites’ blatant attempt at bribery could sway him.[21]. To avoid civil war, the Donati initially left the city, and the Whites emerged victorious. However, the descent into Italy of the King of France, Charles of Valois, changed the situation: although the Whites naively hoped that the King and his 1,200 knights had come to restore order, the Blacks knew well that he had been sent by the pope to eliminate their rivals.

Public Domain

Shortly thereafter, King Charles arrested the leaders of the Whites and allowed the Blacks to return to the city, who for days plunged the city into bloodshed, before moving on to the countryside[22]. Once things calmed down, political trials, requisitions, and forced exiles of the major representatives of the Whites followed. The aftermath of these events lasted a long time, and for years the city tried to find peace while family vendettas were perpetrated through murders and fires that destroyed entire parts of Florence. While many of the old leaders of the Blacks met violent deaths, their families strengthened their grip on power in the city, taking full advantage from the city’s treasury.[23].

The swan song of medieval Florence

The following decades represented, in many respects, the swan song of late medieval Florence. At the peak of its economic power, Florence’s wool production had surged following the crisis in Flanders, producing nearly a tenth of all European cloth. The Arti del Cambio and Calimala lent vast sums of money to the ruling classes across the West, from the papacy to the kingdoms of France and England. [24]

(I covered the economic part a bit more in detail here).

In 1321, the Comapgnia della Misericordia (Company of Mercy) acquired some of the properties of the Adimari family and began the construction of their headquarters, which would later become the Loggia del Bigallo[25]. In the summer of 1334, Giotto began directing the work of the eponymous bell tower in Piazza del Duomo, taking over from Arnolfo di Cambio. In the summer of 1339, work began on the loggia of the Church of Orsanmichele, adorned by mutual agreement with statues of the patron saints of the various Arts[26]. One of the architects of this site, Talenti, also started the construction of the loggia in front of the Palazzo della Signoria, now known as the Loggia de’ Lanzi.

However, the city’s prosperity was marred by its population density and geographical challenges. Chronicler Villani recounts numerous fires, floods, famines, and diseases that struck the weakened population[27]. Militarily, Florence became sluggish, suffering defeats at Montecatini (1315) and Altopascio (1325), which undermined its prestige[28]. To further complicate the situation, the start of the Hundred Years’ War between the King of England and the King of France (both debtors of the Florentines), and the subsequent declaration of insolvency[29], by the former, caused a chain reaction of bankruptcies first among the Mozzi and Scali, spreading than to the major banks of the Bardi, Peruzzi, Acciaiuoli, and Bonaccorsi. These events had severe economic consequences, especially for small savers who had invested their life savings in the major banks. The political situation deteriorated rapidly, leading Florence to entrust the city’s reins to Walter VI of Brienne, the Duke of Athens.

The Duke of Athens

Walter was only formally the Duke of Athens, of course. A nobleman of an ancient French family, he moved to Italy (1342) after his wife’s death, and was then called as podestà to Florence in June of the same year. He began to govern the city as a good old European noble would: with arrogance and an iron fist, without any consideration for the different social environment. A series of abuses, summary justice, and episodes of corruption began (all quite normal at the time), but especially with little regard for the powerful merchant class that had recalled him to Florence. Realizing too late the mistake he made, Walter tried to remedy it by getting himself appointed lord of the city, only to worsen his situation[30].

He indeed promised the Magnati, affected by the Ordinamenti di Giustizia, to restore them to their previous condition once he was made lord of Florence, only then to realize that these families (including the Bardi, Frescobaldi, Cavalcanti, and Donati) would have him in their grip. After discovering a series of conspiracies being plotted against him, he tried to lean on that large slice of the population that was the manual laborers, the subordinates, the workers of the Arte della Lana: in short, all those wage earners forced to a life of hardship by the meager wages granted to them by the merchant class. It was already too late: the Popolo Grasso provoked a series of brawls among the Duke’s soldiers and the population, which rose up with the cry of “Long live the People and the Comune in all their freedom, death to the Duke and his followers!”, and drove Walter out, who fled renouncing the Signoria. The people, however, were not satisfied, and vented their anger against those who had supported the Duke of Athens[31].

The revolt of Ciuto Brandini

This did not serve to calm the crowd, which, remembering Walter’s promises, demanded greater rights and representation, this time with the cry of “Long live the poor commoners, and death to the taxes and the rich!“[32]. The situation soon degenerated, and the houses of the Magnati were set on fire (the first was that of the Bardi family), as did violence in the streets. The crowd then gathered under the figure of Ciuto Brandini, a worker of the Arte della Lana, who promoted the constitution of a “workers’ brotherhood” in opposition to the overwhelming power of the big textile entrepreneurs. For this, on May 24th 1345, he was imprisoned with his sons, and shortly afterwards beheaded[33].

Conclusion

We now have a clearer vision of Florence in the first half of the 14th century. In previous posts, we have discussed social tensions and political struggles, commercial trafficking and economic growth, employment and the difficulties of a rapidly increasing population. All of this, in 1348, would be upset by the most notorious actor of the Crisis of the 14th Century: the Black Death.

References

[1] The division between these two factions has been the subject of extensive study, which I have attempted to summarize here, based on the works of Gaetano Salvemini. I also owe to Salvemini the economic theories presented subsequently. For references, see Salvemini, G. (1974). Magnati e popolani in Firenze dal 1280 al 1295. Feltrinelli, pp.21-63.

[2] “[…]ut de potentibus, nobilibus vel magnatibus de cetero dubietas non oriatur, illi intelligantur potentes, nobiles vel magnates et pro potentibus, nobilibus vel magnatibus habeantur, in quorum domibus vel casato miles est vel fuit a XX citra, vel quos opinio vulgo appellat et tenet vulgariter potentes, nobiles vel magnates“, in Statuto del Capitano del Popolo di Firenze, quoted from Salvemini G., Magnati e popolani, cit., p.25, translation by the author.

[3] Even at that time, the concept of nobility was a subject of heated debate. For a rather well-known example, Dante in the Convivio (1303-1308) writes “domandato che fosse gentilezza, rispuose ch’era antica ricchezza e belli costumi” (Convivio, IV, 4, 6), nly to then change his mind after his exile, when in the Commedia (1312-1321) he condemns “la gente nuova e i sùbiti guadagni” (Commedia, Inferno, XVI, 73). It’s an undoubtedly complex topic and not one to be addressed here. Refer to Barbero, A. (2020). Dante. Laterza, chapter 2.

[4] Salvemini G., Magnati e popolani, cit., p.30, footnote 46.

[5] The Florentie Urbis descriptio of 1339, as cited in Salvemini, gives us 230 moggia per day. The moggio is a volume measurement of Roman origin, which in Florence, at the time, was equivalent to about 584 liters, and the specific weight of soft wheat is 720-740 g/L; thus, it can be deduced that a moggio of wheat weighs approximately 426 kg. With a daily consumption of over 98 tons of wheat for 110,000 inhabitants, we calculate about one kilogram per day per inhabitant: the weight of a homemade loaf of bread. For references see Salvemini G., Magnati e popolani , cit., p.36-37, footnotes 85, 86 and 92. The estimates in kilograms, and any inaccuracies, are my own.

[6] Salvemini G., Magnati e popolani, cit., p.48

[7] “Ritornati i cittadini in Firenze, si resse il popolo alquanti anni in grande e potente stato; ma i nobili e grandi cittadini insuperbiti faceano molte ingiurie a’ popolani, con batterli e con altre villanie”, Compagni D., Cronica delle cose occorrenti ne’ tempi suoi, Libro I, chapter 11. In this context, it’s important to remember that the chronicler Dino Compagni did not have an impartial perspective: he was of the Guelf faction, a wealthy merchant, and on several occasions served as a consul of the Arte di Por Santa Maria.

[8] Pinto G., DELLA BELLA Giano, in “Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani“, Volume 36, Treccani.

[9] Salvemini points out a certain confusion among the chroniclers of the time. For an in-depth analysis, please refer to Salvemini G., Magnati e popolani, cit., pp. 138-159

[10] “contro a’ potenti che facessono oltraggio a’ popolani: e che l’uno consorto fusse tenuto per l’altro; e che i malifìci si potessono provare per due testimoni di pubblica voce e fama: e diliberorono che qualunque famiglia avesse avuti cavalieri tra loro, tutti s’intendessono esser Grandi, e che non potessono esser de’ Signori, né Gonfaloniere di Giustizia, né de’ loro collegi […] e ordinorono che i Signori vecchi, con certi arroti, avessono a eleggere i nuovi” Compagni D., Cronica delle cose occorrenti ne’ tempi suoi, cit., chapter 11. The “Gonfaloniere di Giustizia”, introduced with the Ordinamenti, presided over the Collegio dei Priori (College of Priors) and was the supreme judicial authority of Florence, at the head of the city militia. Compagni knew this well, as from June 15 to August 15, 1293, he himself was the Gonfaloniere.

[11] Compagni D., Cronica delle cose occorrenti ne’ tempi suoi, cit., Libro I, chapter 16

[12] “E chiamoronsi Priori dell’Arti: e stettono rinchiusi nella torre della Castagna appresso alla Badia, acciò non temessono le minaccie de’ potenti: e potessono portare arme in perpetuo: e altri brivilegi ebbono: e furono loro dati sei famigli e sei berrovieri.” Compagni D., Cronica delle cose occorrenti ne’ tempi suoi, cit., Libro I, chapter4

[13] Pampaloni G., Priorato, in “Enciclopedia Dantesca“, Treccani.

[14] Ferroni G., Dante e il nuovo mondo letterario: la crisi del mondo comunale (1300-1380), in Ferroni G. “Storia della letteratura italiana“, vol. 2, Mondadori, p.5

[15] “Queste due parti, Neri e Bianchi, nacquono d’una famiglia che si chiamava Cancellieri, che si divise: per che alcuni congiunti si chiamarono Bianchi, gli altri Neri; e così fu divisa tutta la città“, Compagni D., Cronica delle cose occorrenti ne’ tempi suoi, cit., Libro I, 25. Also Villani tells us that “nacque tralloro per la soperchia grassezza, e per susidio del diavolo, isdegno e nimistà tra ‘l lato di quelli ch’erano nati d’una donna a quelli dell’altra; e l’una parte si puosono nome i Cancellieri neri, e l’altra i bianchi“, in Villani G., Nuova Cronica, cit., Libro Nono, chapter XXXVIII.

[16] “Uomini di basso stato, ma buoni mercatanti e gran ricchi, e vestivano bene, e teneano molti famigli e cavalli, e aveano bella apparenza“, Compagni D., Cronica delle cose occorrenti ne’ tempi suoi, cit., Libro I, chapter 20.

[17] “Erano di grande affare, e possenti, e di grandi parentadi, e ricchissimi mercatanti, che la loro compagnia era delle maggiori del mondo; uomini erano morbidi e innocenti, salvatichi e ingrati, siccome genti venuti di piccolo tempo in grande stato e podere” in Villani G., Nuova Cronica, cit., Libro Nono, chapter XXXIX

[18] “Della casa de’ Donati era capo messer Corso Donati, e egli e quelli di sua casa erano gentili uomini e guerrieri, e di non soperchia ricchezza, ma per motto erano chiamati Malefami” in Villani G., Nuova Cronica, cit., Libro Nono, chapter XXXIX

[19] For a more detailed analysis of the origins and the unfolding of the struggles between the White and Black Guelfs, reference is made to Barbero A., Dante, cit., Chapter11

[20] “Sedea in quel tempo nella sedia di San Piero papa Bonifazio VIII, il quale fu di grande ardire e alto ingegno, e guidava la Chiesa a suo modo, e abbassava chi non li consentia. Erano con lui sua mercatanti gli Spini, famiglia di Firenze ricca e potente: e per loro stava là Simone Gherardi, uomo pratico in simile esercizio; e con lui era uno figliuolo d’uno affinatore d’ariento, fiorentino, si chiamava il Nero Canbi, uomo astuto e di sottile ingegno, ma crudo e spiacevole. Il quale tanto aoperò col Papa per abassare lo stato de’ Cerchi e de’ loro sequaci, che mandò a Firenze messer frate Matteo d’Aquasparta, cardinale Portuense, per pacificare i Fiorentini. Ma niente fece, perché dalle parti non ebbe la commessione volea, e però sdegnato si partì di Firenze” in Compagni D., Cronica delle cose occorrenti ne’ tempi suoi, cit., Libro I, chapter21.

[21] Cardinal Acquasparta decided to leave the city when an anonymous citizen shot a crossbow bolt at his window. To remedy the situation, the Priors attempted the path of corruption, and it was Dino Compagni himself who carried the enormous bribe: “I Signori, per rimediare allo sdegno avea ricevuto, gli presentorono fiorini MM nuovi. E io gliel portai in una coppa d’ariento, e dissi: «Messere, non li disdegnate perché siano pochi, perché sanza i consigli palesi non si può dare più moneta». Rispose gli avea cari; e molto li guardò, e non li volle“. Compagni D., Cronica delle cose occorrenti ne’ tempi suoi, cit., Libro I, chapter20.

[22] “E con tutto questo stracciamento di cittade, messer Carlo di Valos né sua gente non mise consiglio né riparo, né atenne saramento o cosa promessa per lui. Per la qual cosa i tiranni e malfattori e isbanditi ch’erano nella cittade, presa baldanza, e essendo la città sciolta e sanza signoria, cominciarono a rubare i fondachi e botteghe, e le case a chi era di parte bianca, o chi avea poco podere, con molti micidii, e fedite faccendo ne le persone di più buoni uomini di parte bianca. E durò questa pestilenzia in città per V dì continui con grande ruina della terra. E poi seguì in contado, andando le gualdane rubando e ardendo le case per più di VIII dì, onde in grande numero di belle e ricche possessioni furono guaste e arse” in Villani G., Nuova Cronica, cit., Libro Nono, XLIX.

[23] “[Rosso della Tosa] lasciò due figliuoli, Simone e Gottifredi; che dalla Parte furono fatti cavalieri, e con loro un giovane loro parente, chiamato Pinuccio, e molti danari furono donati loro. E chiamavansi i cavalieri del filatoio; però che i danari, che si dierono loro, si toglievan alle povere femminelle che filavano a filatoio” in Compagni D., Cronica delle cose occorrenti ne’ tempi suoi, cit., Libro III, chapter38.

[24] Cardini F., Breve storia di Firenze, cit., p.69-70

[25] Morini U., Documenti inediti o poco noti per la storia della Misericordia di Firenze (1240-1525), 1940,p.1.

[26] Villani G., Nuova Cronica, cit., Libro Dodicesimo, chapter LXVIII

[27] Villani G., Nuova Cronica, cit., Libro Dodicesimo, chapter I, IV, XXII, XXXIII, XXXVI, LXVII, CXIV, CXXVI, to mention only those present in the Libro Dodicesimo, but this type of incident is amply mentioned throughout all the second part of Villani’s work.

[28] Briefly summarized by Cardini (Cardini F., Breve storia di Firenze, p.70), ample and detailed mentions can be found in Villani (Villani G., Nuova Cronica, cit., Libro Undicesimo and Libro Dodicesimo).

[29] Still Cardini F., Breve storia di Firenze, cit., p.71, and also Villani G., Nuova Cronica, cit., Libro Dodicesimo, chapter LV, LXXXIV, e LXXXIII-LXXXVIII

[30] Cardini F., Breve storia di Firenze, cit., p.72, in further detail Villani G., Nuova Cronica, cit., Libro Tredicesimo, chapterI, II, VIII, XVI

[31] For the expulsion of the Duke of Athens, and the lynchings that followed, reference is made to Villani G., Nuova Cronica, cit., Libro Tredicesimo, chapter XVII

[32] “Viva il popolo minuto, e muoiano le gabelle e ‘l popolo grasso!” in Villani G., Nuova Cronica, cit., Libro Tredicesimo, chapter XX

[33] Pinto G., BRANDINI Ciuto, in “Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani“, Volume 14, Treccani.