And here note well, that Italy is the most beautiful manor in the world […] Tuscany is its chamber, for it is the most adorned and orderly part, in which reside the beautiful maidens […] and where secret counsels are made […]. Lombardy is the hall, for there dwell the great powers, and grand banquets are held; indeed, the appetites of the Lombards are often large. Romagna is the garden, all verdant, fertile, and pleasant. The March of Ancona is the cellar, where the sweetest wines of all, oil, honey, and figs are found. Apulia is the stable, where the noblest horses are kept; there is the straw, the hay, the chaff, and the plains of the fields; and there, great battles have been fought on the plains […]. The March of Treviso is the garden of this noble house, with tall trees, flowers, Venice, Verona, and Padua

Benvenuto da Imola, Comentum super Dantis Aldigherij Comœdiam

This is how Benvenuto da Imola described Italy [1] in the mid-fourteenth century: a rustic image, at first comforting and in line with the general perception of medieval economies. However, beneath this idyllic portrayal lies a complex economic transformation that played a crucial role in shaping medieval Italy.

In this post we’ll explore the economic transformations in Medieval Italy, highlighting its unique characteristics, the influence of external factors (like the Crusades), and the significant impact of the power struggle between the Empire and the Papacy on the economic landscape.

Italian Economy in the Early Middle Ages

North Italian

early 10th century

At first glance, the Italian economy of the time may appear predominantly agricultural, with land remaining the central factor of the productive structure, and its cultivation the cornerstone of the economic system. In the Early Middle Ages, the economy was indeed dominated by agriculture, with some small, independent, and self-sufficient landowners, though they were in the minority. Historians suggest that since the 9th century, the Carolingian-inspired curtis (manors) predominated: large plots of cultivated land, sometimes separated, were administratively grouped into agricultural complexes, whether manorial or demesne, managed by a single steward[2] These were quite productive enterprises by the standards of the time. On the one hand, they gradually fragmented into leases and concessions (with corvées becoming scarce); on the other hand, they needed to manage their productive surplus, giving rise to a dense commercial network.

This view challenges the traditional perception of the period as a “dark agricultural world” confined to the poverty of subsistence, only to be suddenly catapulted into the Renaissance. Instead, it reveals an economy that gradually emerged from the difficult centuries following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, evolving into a dynamic network of new cities, navigable waterways, and roads that facilitated the exchange of production surpluses, the establishment of authorities to maintain and secure them, early attempts at currency regulation, and the creation of a network of contacts that shortened the distances between Europe and the Mediterranean[3].

At the turn of the Millennium

From the 9th century, the Italian economy evolved in a manner quite distinct from the rest of Europe. The “barbaric” invasions had tested but not destroyed it. The Lombards quickly integrated and adapted, merging with the Italic populations. Decades of wars and attempted reconquests by the Eastern Roman Empire had starved the region, drastically reducing the population. Yet, the Roman cities remained. With increasingly stable political and social conditions, a growing trend of urbanization began. The rural population moved into the cities, which were safer behind the ancient Roman walls. This growing urban population required sustenance and began importing food from the surrounding countryside. It also began to export tools that were difficult to find in rural areas, such as the ploughshares mentioned in Lombard lords’ inventories[4].

During this period, the Italian peninsula was in a particularly privileged position, with its politically fragmented territories extending to the heart of the Mediterranean. The growing demand for goods strengthened trade, re-establishing relations with Byzantium and the Muslim world. Soon, production of goods that were previously imported began within Italy itself. The demand for domestic consumption was met with the development of increasingly refined processing techniques, so much so that the finished products began to be requested even in the lands from which they were previously imported. This import substitution resulted in a reversal of market positions: paper, initially imported from the Levant, was later produced in Fabriano, in the Marche region, and eventually exported back to the Levant, undermining local paper production there[5].

Development during the Crusades

Guillaume de Tyr, “Histoire de la guerre sainte”, BNF Français 2824 f 173v, 13th century.

In 1095, a new and lucrative commercial opportunity opened up for Italian cities, particularly for the ports: the peregrinatio promoted by Pope Urban II to “liberate” the Holy Sepulchre[6]. This event initiated a massive flow through Italy of people from all over Europe, commonly referred to as the Crusades. Hundreds of thousands of armed pilgrims over the course of decades, each with needs for food and transportation (from the Second Crusade onwards), brought prosperity to cities like Genoa, Pisa, and Venice. Moreover, the trade with the Crusader States, from the capture of Jerusalem in 1099 until the fall of Acre in 1291, significantly enriched these cities.

This period of European territorial expansion established two crucial pillars for the years to come: religious legitimization for military operations and the adoption of economic strategies focused on profit. These aspects can be seen as precursors to the proto-colonial policies later adopted by the “Maritime Republics”[6]. Relations also strengthened with the homelands of these European pilgrims, where Italian merchants acted as bridges for the transfer of money. They connected Europe not only with the Crusader States but also with the Byzantine and Muslim worlds, whose products were in demand and sold as far as Flanders. This region, acting as a northern counterpart to the Mediterranean, had seen its importance grow and surpass that of lower France, due to conflicts, fiscal policies, and the economic development of northern European areas. Traces of stable merchant operations by Italians are found in Flanders, as well as throughout northern France and in England, where Italian merchants facilitated the importation of raw wool and the exportation of textiles[7].

The Influence of the Empire and the Papacy on Italian Economic Development

Two significant entities influenced medieval Italian economic development and the entire political structure of the peninsula: the Empire and the Papacy. From the ashes of Carolingian rule emerged the Holy Roman Empire under Otto I of Saxony, who aspired to make Italy the central element of a broader imperial project. Tensions arose between the Church and the Empire when Otto began his descent into Italy following his coronation as emperor in 962 by Pope John XII[8]. These tensions worsened after Otto’s deposition of the pope and would inflame Italian cities in the centuries to follow.

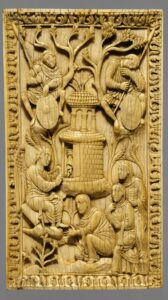

North Italian

ca. 1230–35

Subsequent rulers, such as Frederick II of Swabia, Charles of Anjou, and the Kings of Aragon, poured substantial resources into Italian territories and the coffers of its cities, whether for imperial ambitions or to conquer a part of the Peninsula. On the other hand, the Papacy, from the 10th century, strengthened its grip on the churches of Europe and their vast holdings. As the great ecclesiastical administrative machine took shape, a fraction of the proceeds from every economic activity connected to it was transferred to the coffers in Rome, from the parishes of Spain to the great cathedrals of Germany. To carry out these international transfers, the papacy needed a network of contacts that was reliable, efficient, and widespread: that of the merchants from the Italian cities[9]. One of these cities, perhaps the best documented, was a rising power in central Italy: Florence.

[1] “Et hic nota bene, quod Italia est pulcrior domus mundi, cuius arx, sive caput est Roma, cuius gloriae totus orbis terrarum angustus fuit. Tuscia est eius camera, quia est pars ornatissima et ordinatissima huius domus, in qua morantur pulcrae puellae, sicut in camera; et ubi fiunt secreta consilia, sicut in camera. Lombardia est sala, quia ibi sunt magnae potentiae, ibi fiunt magnifica convivia; amplae enim sunt gulae lombardorum communiter. Romandiola est hortus romanus, tota virens, tota fertilis et amoena. Marchia anconitana est cellarium, quia ibi sunt vina suavissima omnium, olea, mella, ficus. Apulia est stabulum, quia ibi sunt nobilissimi equi; ibi paleae, foena, stramina, camporum planities; et ibi facta sunt magna bella campestria, ut autor iam dixit capitulo XXVIII inferni. Marchia tarvisina est viridarium huius nobilissimae domus, habens arbores altas, floridas, Venetias, Veronam et Paduam”. Benvenuto da Imola, Comentum super Dantis Aldigherij Comœdiam, edited by Lacaita G. F., 5 vols., Firenze, Barbèra 1887, vv. 76-126. Cited in Jones, P., Medieval Agrarian Society in its Prime, edited by Postan M.M., published online by Cambridge University Press, 28 March 2008. (Translation by the author).

[2] For this and the following considerations on Italian agriculture of the time, refer to Zangheri R., L’agricoltura nell’Italia medievale, “Studi Storici”, Anno 8, No. 1 (Gen. – Mar., 1967), pp. 178-190, Fondazione Istituto Gramsci, 1967

[3] For an updated and approachable description of the curtis, refer to Barbero A., Carlo Magno: un padre per l’Europa, Laterza, 2000, XII, 2, a.

[4] Zangheri R., L’agricoltura nell’Italia medievale, cit.

[5] Goldthwaite R. A., The Economy of Renaissance Florence, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009, p. 7.

[6] Mitterauer M., Chapple G., “The Crusades and Protocolonialism: The Roots of European Expansionism”, in Chapple G. (ed.), Why Europe: The Medieval Origins of Its Special Path (Chicago, IL, 2010; online edn, Chicago Scholarship Online, 21 Mar. 2013)

[7] Goldthwaite R. A., The Economy of Renaissance Florence, cit., pp. 8-11.

[8] For further reading, refer to Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: Die Zeit der späten Karolinger und der Ottonen. Krisen und Konsolidierungen 888–1024. Stuttgart, 2008, S. 188; in brief, Treccani, Ottone I detto il Grande, in “Dizionario di Storia”.

[9] Goldthwaite R. A., The Economy of Renaissance Florence, cit., p.p. 9-22.