“I say, then, that the years of the beatific incarnation of the Son of God had reached the tale of one thousand three hundred and forty-eight, when in the illustrious city of Florence, the fairest of all the cities of Italy, there made its appearance that deadly pestilence”.

Giovanni Boccaccio, Decameron, 8

That’s how Giovanni Boccaccio [1] tells us the Black Death’s arrival in Florence, having returned to the city years earlier due to the economic turmoil caused by the failure of the great Florentine banks. Through words like his, we aim to summarize the phenomenon of this plague in its first wave (1347-1353), a pandemic that killed as many as 50 million people, roughly half of Europe population at the time.

However, before we begin, we must step away from these areas and delve into the medical realm: to understand the consequences of the Plague we must first examine what it was (or rather, what it still is), how it spread, and finally manifested.

Understanding the Black Death

According to the most widespread opinion, the Plague is a zoonotic infection caused by the bacterium Yersinia Pestis, studied by Kitasato S. and Yersin A., the latter of whom isolated it during the Hong Kong epidemic of 1894[2]. In humans manifests primarily in three syndromes: bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic[3].

Etiology

From an etiological point of view, Y. Pestis turns out to be the evolution, over the millennia, of the bacillus Yersinia Tuberculosis[4], enzootic in rodents and transmitted through parasitic insects, mainly fleas. The disease is transmitted to humans usually through the bite of these fleas, as well as the bite of infected animals, direct handling of infected meat by people with open skin lesions, inhalation of nebulized bacteria, consumption of infected animals, or among humans.

Once it enters the human host, after an incubation period of 2-8 days, Y. Pestis rapidly spreads throughout the body, causing the sudden onset of fever, chills, headache, and a widespread sense of weakness; the face takes on the typical characteristics of the pestilential facies with shiny eyes and dry lips. It then attacks the lymphatic system, causing extraordinarily intense pain and swellings, generally in the inguinal, axillary, and cervical areas. Because of the involvement of the lymph nodes, these swell up, manifesting as single (or clusters) of buboes: the most known and visible form of the Plague.

If the lymphatic barrier holds, there is gradual improvement and recovery. In the majority of untreated cases, however, this does not happen: the barrier breaks down and the pathogens spill into the blood, and generally, the host’s death follows.

“All organs can be the site of haemorrhage”[5]. If the form is septicemic, the bubo does not manifest; if it is pneumonic (or the abscess damages the lung tissue) similarly the bubo may not present, but the bacterium can spread through the air via the host’s expectoration. Of all these symptoms, we find testimony in many sources of the time, as we will soon discuss.

Origins of the Black Death

The Mediterranean people were not new to this type of calamity. Although various epidemics had shaken populations over the centuries (the Plague of Athens narrated by Thucydides [6], or the Antonine Plague reported by Galen [7]), according to scholars, a variant of Y. Pestis made its appearance for the first time in 541 in the territories of the Eastern Roman Empire.

The symptoms described by Procopius [8] appear entirely similar to the medieval epidemic, and recent studies [9] confirm the same origin for both: the Asian steppes, where it manifested again in those lands around 1340-45.

It is interesting to dwell again on the extent of the commercial traffic of the time, because it is through caravan and maritime routes that we can trace the spread of the disease. Four main routes [10] connected the East and West: two by land, through the current areas of Siberia and Iran; two by sea, along the coasts of India and the Red Sea. All of them then fragmented into other trade routes, which extended towards the Mediterranean, and then spread throughout Europe. It is through one of these that, as the sources of the time confirm, the epidemic spread.

The Black Death reaches Italy

In 1343, the city of Caffa (modern Feodosia, Ukraine), an important commercial hub on the shores of the Black Sea, was besieged by the Golden Horde of Ganī Bek, coming from the Asian steppes [11]. Caffa was a Genoese colony and faced the sea: this on one hand prolonged the siege, on the other gave a reasonably safe escape route to the besieged population.

The siege lasted a long time, and the disease spread, first among the besieging troops and then in the city itself, decimating the population. Two Genoese galleys, in 1346, left the now plague-ridden city, bringing the disease along the familiar trade routes through the Black Sea, finally reaching Constantinople[12]. The plague struck the Byzantine metropolis in 1347, then spreading to various coastal cities of the northern Mediterranean[13].

The Genoese merchants attempted to escape the approaching disease gain, and turned to Italy, landing in Messina in October 1347 [14]. From Sicily, due to its strategic position in the trade domain, a series of routes unfolded that then brought the Plague to North Africa (Tunis), to the Mediterranean islands (Corsica, Sardinia, Balearics), and to all of southern Italy.

Naples was severely affected, and even more so Amalfi, where there were “more dead than alive”[15]. With the spread of the disease in Sicily, from there merchants set off seeking refuge in Pisa[16] first and Genoa later, unknowingly bringing the Plague with them, which in the following year would spread throughout the peninsula[17].

Florence and the Black Death

(this topic is covered a bit more in detail here)

The Florentines of the time were already aware of the disease’s origin and especially of its rapid approach[18]. They did everything possible to stop it, but the living conditions and city policies were in such a state that the measures would prove ineffective.

The majority of the population, in fact, was in a worse state than at the beginning of the fourteenth century: a series of famines (including the Great Famine of 1315-17) had repeatedly struck the European territory, giving rise, among other things, to three distinct phenomena: malnutrition among the lower classes of the population[19], a drastic increase in the prices of foodstuffs, and migration from the countryside to urban centers, where food was habitually distributed to the needy[20].

Regarding the migration to the city, we resume here what was said in the previous chapter: over the previous decades, a process of strong urbanization had occurred, which had caused a rapid growth of processing activities within the city walls and of population density, from which soon derived a lowering of the already precarious hygienic conditions. It is easy to imagine that, compared to modern standards, hygiene in the Middle Ages was poor [21]; but it was so precarious for the Florentine lower class, that in the early fourteenth century a series of measures were taken by the authorities[22], aimed at improving the situation that had become intolerable.

When the news of the plague in Messina spread, the observance of such hygienic rules was again imposed, from which the previous non-compliance of the same can be deduced. After all, the categories of workers who, to respect the rules, would have had to limit their activities, or bear expenses to adapt them, were the same ones that were represented by the top of the city administration. The manifestation of an archaic conflict of interest is evident.

They attempted to enforce them only when, in 1348, the severity of the situation began to be understood:

“the cleansing of the city from many impurities by officials appointed for the purpose, the refusal of entrance to all sick folk, and the adoption of many precautions for the preservation of health”[23].

Knowing the spread of the disease in the ports of central-northern Italy, attempts were made to take action: a decree of April 3, 1348, imposed the prohibition of coming into contact with Pisans and Genoese, and on April 11, a group of eight experts was formed to delegate the health of the city[24].

The documents of those days have been lost, but the examination of those from the nearby city of Pistoia [25] can give us an idea of the attempts made: the entry into the city of used fabrics was prohibited, one should not enter the houses where there had been deaths, whose remains would have been carried out of the houses in closed coffins, without funeral procession, and buried in deep pits specially dug. It was forbidden to wear mourning except for widows, to announce funerals and to ring the death bells. Measures, therefore, aimed at a dual purpose: to reduce occasions for gathering on the one hand, to hide as much as possible the manifestations of public grief on the other. It was all in vain.

Briefly slowed down by the rigor of winter, with the arrival of spring it spread in the city of Florence[26], and “the mortality was horrible and cruel thing… and it is not possible for human language to count [27]”.

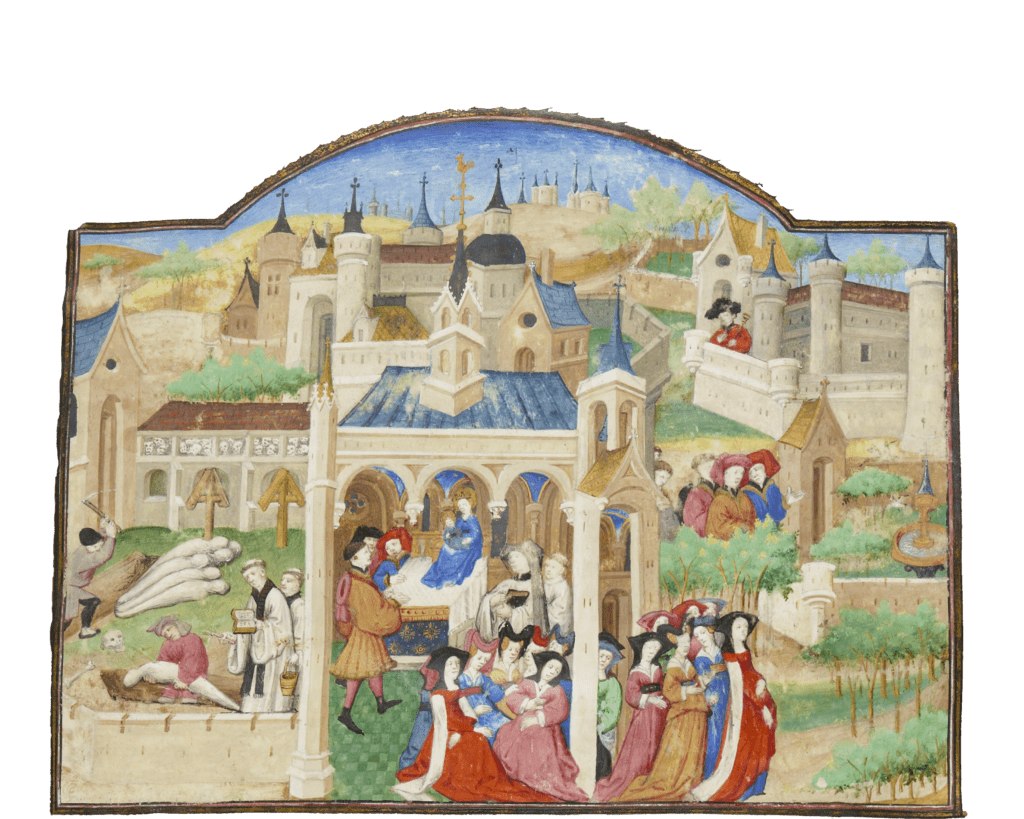

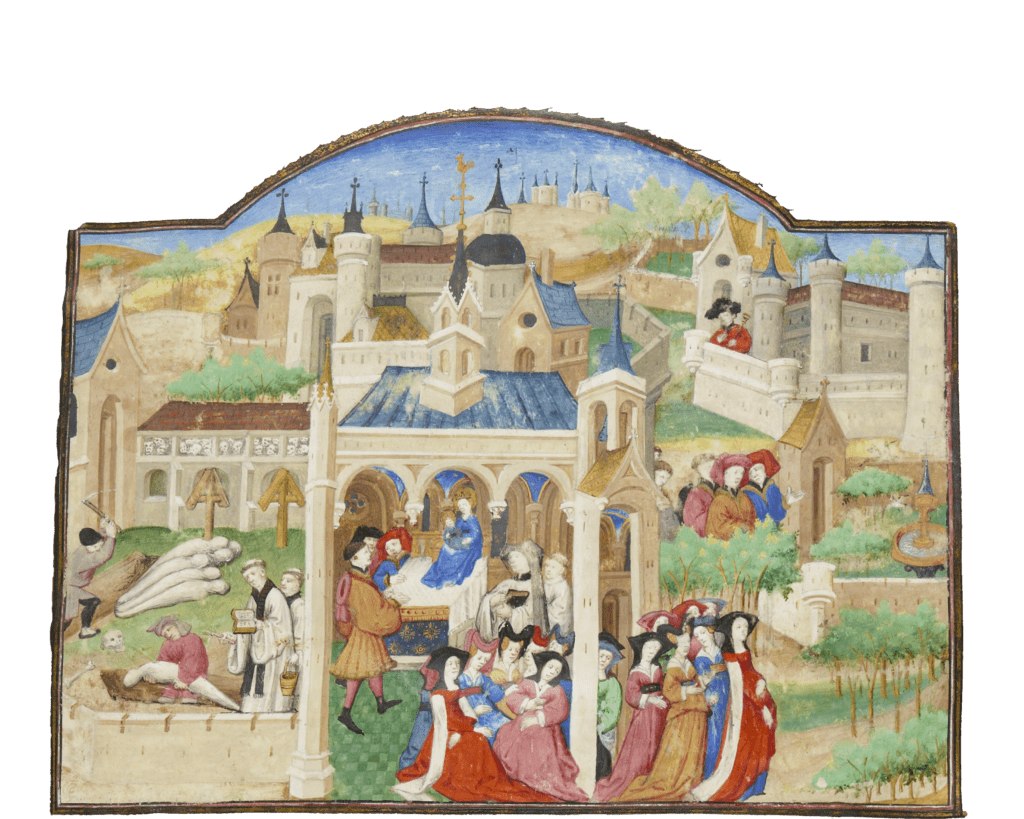

Manuscript “Français 239”, f. 1r

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits

Bibliothèque nationale de France

References

[1] Boccaccio G., Decameron, , 8, translated by Rigg J. M., London, 1921 (first printed 1903).

[2] Yersin A., La peste bubonique a Hong-Kong, in “Annales de l’Institut Pasteur: Journal de microbiologie“, 1894, p. 662.

[3] For every medical definition of the Plague, here and in the following pages, please refer to Dillard R. L. e Juergens A.L., Plague, StatPearls Publishing, in “National Library of Medicine: National Center for Biotechnology Information“.

[4] Over the last century, and especially in the recent years, the historical debate regarding the origins of the Plague has been extensive, enriched by a variety of often conflicting theories. Eminent scholars have utilized the theories of their time to provide a scientific explanation for the phenomenon, including Shrewsbury, Ziegler (see Shrewsbury J. F. D., A History of Bubonic Plague in the British Islands, Cambridge University Press, 1970 and Ziegler P., The Black Death, Collins, 1972, mentioned in Bergoldt K., Der Schwarze Tod in Europa, Verlag, 1997) and Bean (refer to Bean J. M. W. et al, The black death: the impact of the fourteenth-century plague, ed. Williman D., introduction by Siraisi N., in “Papers of the Eleventh Annual Conference“, Center for Medieval & Early Renaissance Studies, 1982), whose theories are still quite widespread. However, in the author’s opinion and in light of recent scientific discoveries, some doubts should be dispelled.

All pathogenic variants of Y. Pestis currently in circulation owe their origin to medieval epidemics; similarly “the perceived increased virulence of the disease during the Black Death may not have been due to bacterial phenotype“, suggesting that a series of other factors, which we will briefly discuss in further posts, need to be considered. It would not be about different variants (bubonic, pneumonic, septicemic) but, as mentioned later in the text, three different symptoms of the same infection. The doubt, however, remains, and the different symptomatologies expressed by fourteenth-century authors (including those mentioned in this chapter) can be explained by “either the presence of multiple strains […] or microevolutionary changes accruing in one strain, which is known to occur in disease outbreaks“.

It is interesting to note a main difference between the buonic plague as it presents today and its fourteenth-century manifestation: the rate of spread of infections. While modern variants still have a lethality of between 50 and 90% (understood as the percentage of deaths from untreated infections), their spread remains extraordinarily contained. Taking the example of Madagascar, where the Plague is endemic, there were 13,234 cases in eighteen years, from 1998 to 2016, out of 25.5 million inhabitants: thus, about 0.5% of the population was infected. Nothing, compared to medieval Europe, where the first wave of the Plague is not estimated in terms of the infected, but is believed to have caused the death of 30 million people, 38% of the population, in five years.

A possible explanation is the drastic improvement in global hygiene conditions compared to those of the time, as we will mention in the chapter. It is comforting to know that, although “the pathogen implicated in the Black Death has close relatives in the twenty-first century that are both endemic and emerging“, no existing variant of Y. Pestis has the same genetic profile as the medieval form.

Although we can say that we have reached a good level of “certainty” about the disease that struck Europe from the fourteenth century, historians who had studied the disease more thoroughly than the author were equally certain. Therefore, we can only wait for scientific research to dispel our doubts once and for all. In conclusion, the responsibility for these opinions obviously lies with the author, while for scientific research, reference is made to recent genetic studies conducted on the remains of those who died of the Plague at East Smith (London), entombed between 1348 and 1349. For further reading, as well as all the quotes in this note, please refer to Bos, K. I. et al., A draft genome of Yersinia Pestis from victims of the Black Death, in “Nature“, vol. 478 (7370), 2011, p.506-510.

[5] “Tutti gli organi possono essere sede di emorragia”, AA.VV., La peste nera (1347-1350), Università degli Studi di Firenze, Seminario di Storia medievale, Relazioni degli studenti, a.a. 1969/1970, Eurografica, 1970, pp. 41-104., mentioned in AA.VV., Morire di peste: testimonianze antiche ed interpretavioni moderne della “peste nera” del 1348, edited by Capitani O., Patròn Ed., 1995, p.103.

[6] Thucydides, Περὶ τοῦ Πελοποννησίου πoλέμου, edited by Jones H. S., in “Historiae”, Oxford University Press, 1910, ΙΣΤΟΡΙΩΝ Β or Book II, p.7. Typhoid fever was probably the cause, according to publications by Papagrigorakis M. J. et al., DNA examination of ancient dental pulp incriminates typhoid fever as a probable cause of the Plague of Athens, in “International Journal of Infectious Diseases“, vol. 10, n. 3, 2006, pp. 206–214.

[7] Others believe it was likely measles, or even smallpox (H. Haeser, in Lehrbuch der Geschichte der Medicin und der epidemischen Krankenheiten, 1882 Vol. 3, p.24–33). Galen witnessed the pestilence decimating Roman legions when Emperor Marcus Aurelius recalled him to Aquileia in 168-169. This is recorded in many of his writings, including the Θεραπευτικὴ μέϑοδος, though specific passages were challenging to pinpoint for the Author due to the vastness of Galen’s work. For comprehensive review, consult the complete works (Galeni opera omnia, a cura di Kühn K. G., Cnoblochii, 1821-1833) archived at Université Paris Cité, Bibliothèque Numérique Medica.

[8] Procopius, Ὑπὲρ τῶν Πολέμων Λόγοι, in “Opere”, Tomo II: Istoria delle Guerre Persiane, translated to Italian by Giuseppe Rossi, Libro II, Capo 22, Molina, 1833.

[9] Morelli G., et al., Yersinia pestis genome sequencing identifies patterns of global phylogenetic diversity, in “Nature genetics“, vol. 42, 12, 2010.

[10] Chanu P., L’expansion européenne du XIII au XV siecle, Paris, 1969, p.90, mentioned in in AA.VV., La peste nera (1347-1350), cit., in AA.VV., Morire di peste, cit., p. 134.

[11] Benedictow O. J., The Black Death, 1346-1353: The Complete History, The Boydell Press, 2004, pp.50-51; and also Ziegler P. and Deaux G. mentioned in AA.VV., La peste nera (1347-1350), cit., in AA.VV., Morire di peste, cit., p. 135

[12] Corpus Chronicorum Bonensium, in “Rerum Italicarum Scriptores”, 2nd edition, t. XVIII, part 1, vol. 2, p. 585, mentioned in AA.VV., Morire di peste, cit., p. 136

[13] “Una testimonianza della devastazione che la peste operò, ci viene offerta dall’imperatore Giovanni Cantacuzeno, il quale nota che l’epidemia colpì, in maniera rilevante, tutte le zone costiere: Ponto, Tracia, Macedonia, Grecia, Italia, Siria, Egitto, Libia e Giudea” AA.VV., La peste nera (1347-1350), cit., in AA.VV., Morire di peste, cit., p. 135.

[14] Del Grasso, A. di Tura, Cronaca senese, p. 553, and also Ziegler P. e Deaux G., mentioned in AA.VV., Morire di peste, cit., p. 137.

[15] Chronicon Estense, p. 162, and “plus mortui quam vivi” in Corradi A., Annali delle epidemie, p.41, metioned in AA.VV., La peste nera (1347-1350), cit., in AA.VV., Morire di peste, cit., p. 139. Translation by the author.

[16] “negli anni 1348, alla entrata di gennaio, venne a Pisa due galee di genovesi, le quali vennero di Romania, et chome furono giunte alla piaza del pesce, qualunque persona favellò a quelli delle decte due galee, si subito si era ammalato et morto”, Sardo R., Cronaca di Pisa, p.96, in AA.VV., La peste nera (1347-1350), cit., in AA.VV., Morire di peste, cit., p. 135.

[17] “Questa pestilenzia si venne di tempo in tempo gente apprendendo, comprese infra il termine d’uno anno la terza parte del mondo che si chiama Asia. […] E in quello tempo galee d’Italiani si partirono del Mare maggiore, e della Soria e di Romania per fuggire la morte, e recare le loro mercatanzie in Italia: e’ non poterono cansare, che gran parte di loro non morisse in mare di quella infermità. E arrivati in Cicilia conversaro co’paesani, e lasciarvi di loro malati, onde incontanente si cominciò quella pestilenzia ne’ Giciliani. E venendo le dette galee a Pisa , e poi a Genova, per la conversazione di quegli uomini cominciò la mortalità ne’detti luoghi, ma non generale. Poi conseguendo il tempo ordinato da Dio a’ paesi, la Cicilia tutta fu involta in questa mortale pestilenzia […] e negli anni di Cristo 1348 ebbe infetta tutta Italia” in Villani M., Cronica, Moutier, 1825, Tomo I, p.6

[18] “Cominciossi nelle parti d’ Oriente, nel detto anno [1346], inverso il Cattai e l’India superiore, e nelle altre provincie circustanti a quelle marine dell’oceano, una pestilenzia tra gli uomini d’ogni condizione di catuna età e sesso, che cominciavano a sputare sangue, e morivano chi di subito, chi in due o in tre dì, e alquanti sostenevano più al morire” in Villani M., Cronica,cit., p.5. Also Boccaccio tells us how “alquanti anni davanti nelle parti orientali incominciata, quelle d’innumerabile quantità di viventi avendo private, senza ristare d’un luogo in uno altro continuandosi, inverso l’Occidente miserabilmente s’era ampliata”, in Boccaccio G., Decameron, cit., p.10.

[19] “carestia non è sinonimo di peste […] può essere però considerata come fattore favorente lo sviluppo di una epidemia, ma di una qualsiasi epidemia” in AA.VV., La peste nera (1347-1350), cit., in AA.VV., Morire di peste, cit., p. 159.

[20] The distribution of alms to the poor in the form of food was common in cities of the time. Though later, an interesting depiction is provided by the lunette frescoed by Alessandro Allori and Ludovico Buti, visible in the bookshop of the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence.

[21] “la sporcizia abbondava non solo nelle case […], ma anche nelle strade. […] la stessa veste veniva indossata per mesi […] poi pensiamo che il re d’Inghilterra faceva il bagno una volta alla settimana e che spesso se ne dimenticava, possiamo ben immaginare come questa funzione fosse del tutto estranea alle classi inferiori” in AA.VV., La peste nera (1347-1350), cit., in AA.VV., Morire di peste, cit., p. 162.

[22] “Nei primi anni del XIV secolo con un decreto si vietava di esercitare all’interno della città qualsiasi industria emanasse un cattivo odore […] ai galigai e ai pergamenai fu imposto di scavare dei canaletti per il deflusso delle acque sporche; ai tintori di praticare canali sotterranei per le orine di cui si servivano. […] Nel 1319 le autorità vietarono che si macellassero per le vie, buoi, montoni e suini e che il sangue scorresse sul lastrico e le interiora marcissero qua e là” in AA.VV., La peste nera (1347-1350), cit., in AA.VV., Morire di peste, cit., p. 130.

[23] Boccaccio G., Decameron, 10, translated by Rigg J. M., London, 1921 (first printed 1903).

[24] “i padri, vedendo la grandezza del male, benché fossero grandemente sbigottiti … formarono un ufficio di otto cittadini per un anno per provvedere alla polizia della città si per le strade come per le case”, Ammirato S., Istorie Fiorentine,vol. I, 1647, p. 505-506, mentioned in AA.VV., La peste nera (1347-1350), cit., in AA.VV., Morire di peste, cit., p. 125.

[25] Chiappelli A., Gli ordinamenti sanitari del comune di Pistoia contro la pestilenza del 1348, in “Archivio storico Italiano”, serie IV, n. 58, Tomo XX, 1887, pp.3-24, mentioned in AA.VV., La peste nera (1347-1350), cit., in AA.VV., Morire di peste, cit., p. 126.

[26] “Nella nostra città cominciò generale all’entrare del mese d’aprile gli anni Domini 1348“, in Villani M., Cronica, cit., p.8., and also Bonaiuti B., a.k.a. Marchionne di Coppo Stefani, in Istoria Fiorentina, Rub. 634, in “Delizie degli Eruditi Toscani“, a cura di Di San Luigi I., Tomo XIII, Gaet. Cameiagi Stampator Granducale, 1780, p. 135 and following.

[27] “la mortalità fu orribile e crudel cosa … e non è possibile a lingua umana a contare”, Di Tura del Grasso A., Cronaca senese, in “Rerum Italicorum Scriptores”, 2nd ed.., t.XVI, part 6, p.555, mentioned in in AA.VV., La peste nera (1347-1350), cit., in AA.VV., Morire di peste, cit., p. 141. Translation by the author.